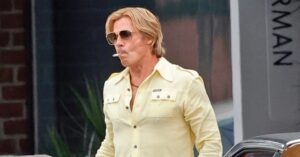

Tom Cruise is not just a movie star.

He is also a stunt performer in a leading man’s body.

For decades, he has pushed action cinema toward something rarer and more thrilling: real risk, carefully managed by elite professionals, captured on camera with almost no cheats.

That commitment is a major reason the Mission: Impossible films feel different from many modern blockbusters.

They look physical.

They look expensive.

Most of all, they look believable.

When people talk about Tom Cruise’s wildest moments, they often mention hanging from the side of a plane, climbing the Burj Khalifa, or riding a motorcycle off a cliff.

Yet many stunt experts and fans point to a different peak of danger and complexity.

It is the HALO jump in Mission: Impossible – Fallout.

If you want a quick official overview of the film, you can start with the Mission: Impossible – Fallout page.

But the real story is what happened behind the scenes, and why this one sequence became a gold standard for practical action.

Why Tom Cruise Doing His Own Stunts Matters

Action movies have always used doubles.

There is nothing wrong with that.

Stunt performers are highly trained specialists, and they deserve credit for building the language of screen action.

What is unusual is a top-billed actor repeatedly choosing to do the most dangerous portions himself.

Tom Cruise’s decision changes how scenes are planned.

It changes how they are filmed.

It changes how audiences feel while watching.

When the camera stays close and you can clearly see an actor’s face, the tension rises naturally.

Your brain understands the difference between “movie danger” and “real danger.”

That is why his stunts have become part of the franchise’s marketing.

They are also part of its identity.

In a world of digital effects, Cruise makes a bold promise: “We actually did it.”

That promise, however, creates a big challenge.

The crew must design stunts that are spectacular but also repeatable and survivable.

They must build layers of safety without destroying the realism.

They must also accept that the star is a key piece of the physical machine, not just the person delivering lines.

For background on the series itself, the Mission: Impossible franchise history shows how each film tried to top the last.

But the HALO jump is the moment where “topping” became almost scientific.

What Is a HALO Jump, in Simple Terms

HALO stands for High Altitude, Low Opening.

It is a real skydiving technique used by military forces.

The jumper exits an aircraft at a very high altitude.

They freefall for a long time.

They open the parachute much lower than in typical civilian skydives.

The goal in military operations is often to reduce detection and reach a target quietly.

In filmmaking, the goal is different.

The goal is to capture the feeling of extreme altitude, speed, and isolation.

The problem is that a real HALO jump is not “safe” in the way most movie stunts are.

It is manageable only with training, planning, and strict conditions.

It also includes invisible threats that are easy to underestimate, like oxygen deprivation and freezing temperatures.

Even before you add cameras, lights, and performance requirements, it is already a demanding operation.

To understand the basics of parachuting and safety standards, many people start with general skydiving information from the United States Parachute Association.

That context helps you appreciate how far a film set must go to do something like this responsibly.

The HALO Jump in Mission: Impossible – Fallout

In Fallout, the HALO jump is not just a quick cutaway.

It is a full cinematic set-piece.

It has story pressure.

It has atmosphere.

It also has close-up acting while falling through the sky at high speed.

That last part is the key.

The sequence needed more than a wide shot with a tiny body in the clouds.

It needed Tom Cruise’s face, his movement, and his character’s urgency.

That requirement makes the stunt dramatically harder.

The moment you demand close-up footage during freefall, you introduce strict camera needs.

You also introduce timing needs.

You also increase risk.

Because now the performer must “act” while managing oxygen, body position, speed, and spatial awareness.

And the camera flyer must be close enough for the shot while staying safe.

If you want a general look at Cruise’s career arc that led to this kind of creative control, his profile on Britannica is a useful starting point.

It helps explain why few stars are in a position to attempt something this complex.

Why This Stunt Was Considered the Most Dangerous

People often assume the most dangerous stunts are the ones that look the craziest.

Sometimes that is true.

But danger is not only about spectacle.

Danger is about variables you cannot fully control.

Danger is about small failures becoming catastrophic.

A HALO jump is filled with such variables.

Altitude is unforgiving.

Weather is unpredictable.

Visibility changes fast.

Human bodies react differently under stress and cold.

Equipment must work perfectly.

Timing must be precise.

In a normal skydive, if something feels off, you can usually adjust your plan.

In a HALO jump designed for a film shoot, the window for adjustment can be smaller.

Because you are trying to capture specific beats on camera.

Because the aircraft has a schedule.

Because the light is changing.

Because the shot list is demanding.

Because the story needs continuity.

All of that pressure sits on top of a stunt that already carries serious risk.

High Altitude Problems: Oxygen and Awareness

At very high altitude, the air is too thin for normal breathing.

That means supplemental oxygen is required.

Oxygen systems add complexity.

They add failure points.

They also add a performance challenge, because breathing equipment changes how you move and how you look on camera.

Lack of oxygen can cause confusion and slow reactions.

In a stunt where awareness and timing are life-saving, that is a major concern.

Freezing Temperatures and Physical Control

High altitudes are extremely cold.

Cold can affect muscles and coordination.

Cold can also affect equipment.

When your body stiffens, fine motor skills become harder.

That matters when you must control a stable fall position, hit marks in the air, and prepare for a low parachute opening.

“Low Opening” Means Less Time to Fix Mistakes

The “LO” in HALO is what makes the jump so intense.

Opening the parachute low reduces the margin for error.

It leaves less time to respond if something goes wrong.

It also makes timing more critical.

On film, timing is already king.

In the sky, timing is survival.

Filming Adds Another Layer of Risk

To capture the stunt, you need camera operators in freefall.

You need them close.

You need them stable.

You need them synchronized with the performer.

That turns one dangerous activity into a coordinated aerial dance.

If you are curious about how demanding aerial coordination can be in general, the basics of aviation safety and human factors are often discussed in public resources like the FAA site.

Even though filmmaking is not aviation training, the underlying lesson is the same: complex systems require disciplined procedures.

Training, Preparation, and the Reality of “Doing It for Real”

Tom Cruise did not wake up one day and decide to jump out of a plane from extreme altitude for fun.

This type of stunt requires serious preparation.

Professional skydivers spend years building skills.

They repeat drills until reactions become automatic.

They learn how to read wind, body position, and altitude without panic.

For a film stunt, the training must also include camera awareness and performance beats.

That is a different kind of practice.

It is not just “survive the jump.”

It is “survive the jump while delivering the shot.”

That difference is why the HALO jump stands out.

The goal was not simply to claim a record.

The goal was to build a sequence that felt immediate and real to the audience.

And because Cruise is the face of the franchise, the audience needed to see him clearly.

How the Scene Creates Suspense on Screen

The HALO sequence works because it is not only technical.

It is cinematic.

It has tension before the jump.

It has tension during the fall.

It has tension when the plan starts to shift.

The viewer feels the stakes because the scene is paced like a mini-thriller.

The sound design helps, too.

Breath becomes loud.

Wind becomes aggressive.

The world feels huge and empty.

That emptiness makes the danger feel personal.

There is also a psychological trick at play.

When a movie shows a real human body falling through real clouds, your mind reacts differently than it does to a fully digital shot.

The movement has imperfections.

The light behaves naturally.

The camera struggles just enough to feel truthful.

That “truth” is what makes you lean forward.

It is entertainment built from authenticity.

The Marketing Effect: When Stunts Become the Story

Mission: Impossible has turned stunt craft into a key part of its brand.

The audience expects a “how did they do that?” moment.

With the HALO jump, the answer is simple and wild: they did it for real.

This strategy is clever, but it is also risky.

When you market real danger, you must deliver it responsibly.

You cannot encourage reckless imitation.

You also cannot ignore safety culture.

The production must communicate that these are controlled operations done by experts.

That balance is why Cruise’s stunt reputation is both admired and debated.

Admired, because it restores respect for practical filmmaking.

Debated, because it raises ethical questions about how far a production should go when a star’s body is part of the product.

A Critical Look: Is This Kind of Risk Necessary?

It is fair to ask whether real extreme stunts are necessary for great action.

Many amazing action sequences are created with smart editing, choreography, and visual effects.

A film does not need real danger to be exciting.

So why pursue it?

One answer is creative identity.

Mission: Impossible sells “realer than real” action.

Another answer is audience fatigue.

Viewers have seen endless CGI destruction.

Practical stunts cut through that noise.

They feel like events.

There is also a craft argument.

When a stunt is real, other departments level up.

Cinematography becomes more precise.

Lighting becomes more strategic.

Sound design becomes more grounded.

Editing can hold shots longer, because the footage can take it.

That said, real risk should never be romanticized.

A production can respect stunt culture and still question escalation.

At some point, the law of diminishing returns appears.

A stunt can become so dangerous that the “extra realism” is not worth the potential cost.

The HALO jump sits right on that edge, which is why it fascinates people.

It is impressive.

It is also unsettling if you think about what could go wrong.

How the HALO Jump Changed Expectations for Action Films

After Fallout, audiences became more aware of stunt authenticity.

They started asking whether a sequence was practical or digital.

They paid attention to behind-the-scenes training.

Studios noticed this, too.

Authenticity became a selling point again.

Not for every movie, but for a certain type of action film that wants credibility.

Cruise’s approach also highlighted something important about modern blockbusters.

Spectacle alone is not enough.

The best action is a mix of clarity, danger, and character.

The HALO sequence has all three.

You can follow what is happening.

You can feel the risk.

You can understand why the character is doing it.

That combination is why the stunt is remembered as more than a headline.

It is remembered as storytelling.

Other Tom Cruise Stunts, and Why the HALO Jump Still Stands Tall

Tom Cruise has a long list of famous stunts.

He climbed the Burj Khalifa in Ghost Protocol.

He held onto the outside of an aircraft during takeoff in Rogue Nation.

He performed intense helicopter flying in Fallout.

He has built a career on pushing the boundary between actor and stunt professional.

Yet the HALO jump is unique because it combines extreme environment, limited margins, and performance demands all at once.

It is not a single physical feat like “climb this.”

It is a system feat like “survive this precise sequence under harsh conditions while filming a close-up.”

That is why many people call it the most dangerous.

Not because it is the loudest.

Because it is the most unforgiving.

What Viewers Can Learn From Watching This Sequence

The HALO jump is entertaining, but it also teaches media literacy.

It reminds viewers that filmmaking is engineering plus art.

It shows how planning creates freedom.

It demonstrates that “realism” is often a choice, not an accident.

It also encourages appreciation for the hidden professionals behind the camera.

Even if the star is the one jumping, teams of experts make the jump possible.

They plan safety.

They manage equipment.

They track weather.

They coordinate aircraft and timing.

They rehearse.

They adapt.

So when you watch the sequence again, it can be fun to watch it twice.

First, watch it as a story moment.

Then, watch it as a craft moment.

Look at the framing.

Look at how long the shots hold.

Listen to how sound builds pressure.

Notice how the scene uses the sky as a set, not just a background.

Final Thoughts: The HALO Jump as a Modern Action Landmark

Tom Cruise’s reputation for doing his own stunts is not hype.

It is a defining feature of his work.

The HALO jump in Mission: Impossible – Fallout stands as the most dangerous symbol of that commitment.

It combined real high-altitude freefall, strict timing, harsh conditions, and close-up storytelling.

It delivered an action sequence that feels both spectacular and strangely intimate.

Whether you view it as brave, extreme, or borderline insane, it is hard to deny its impact.

It raised the bar for practical action.

It also reminded audiences that sometimes the most exciting special effect is a real human doing something real, with a camera brave enough to follow.

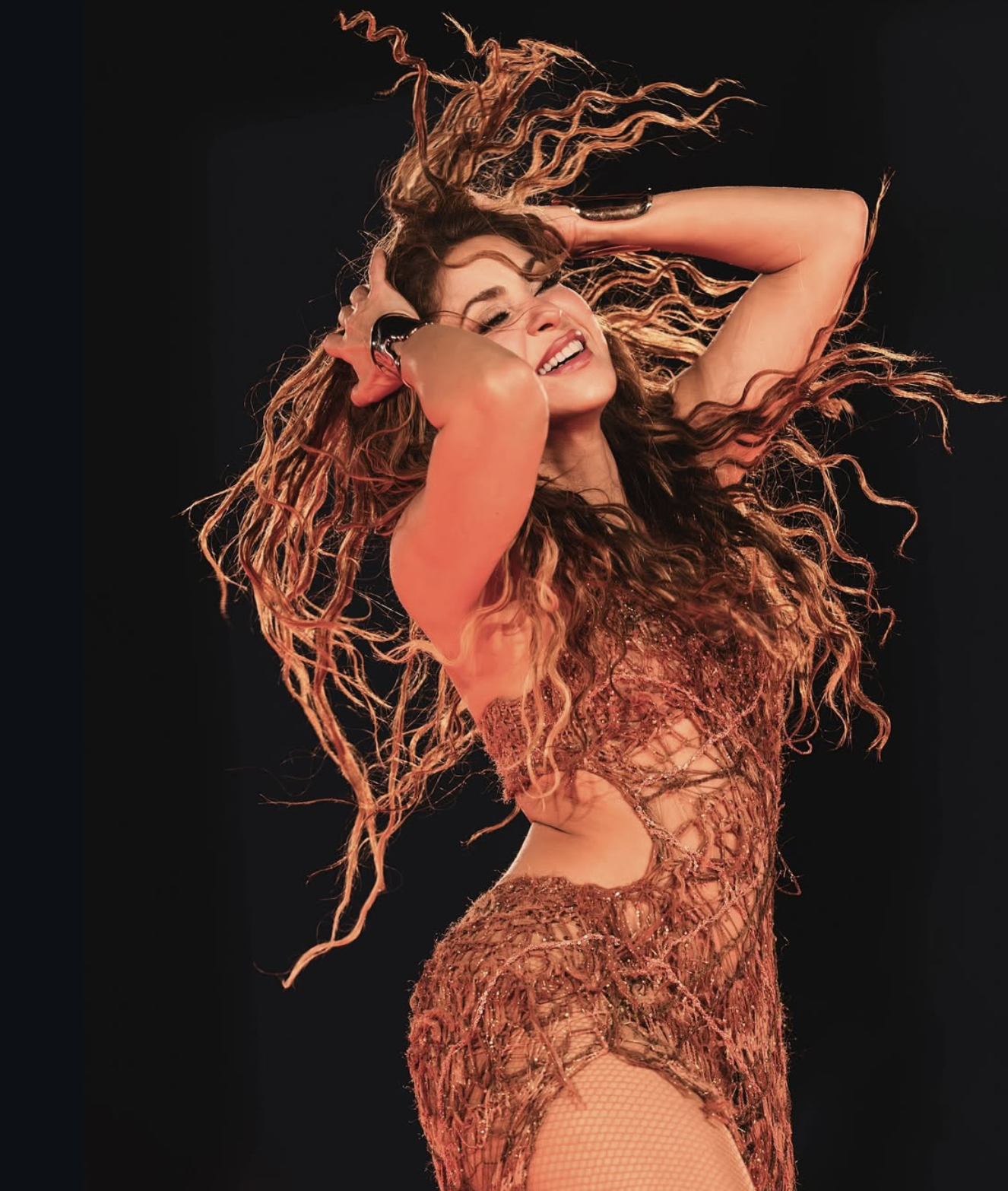

Also Read : Shakira’s Boston concert called off hours before show.